Fraternity

- 1714 Hinman Ave. Evanston, IL 60201

- headquarters@sigmachi.org

- Directory

Ryan Liskey, MARQUETTE 2010

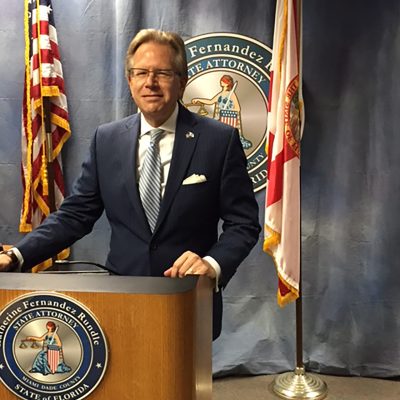

A Southern Methodist Sig’s efforts help clean up public corruption in south Florida

“If you see something you can either ignore it, tell somebody or take some action,” says Michael Kesti, SOUTHERN METHODIST 1983. The South Florida-based lobbyist and chairman of the Governmental Relations Group has opted for the latter two of those three options for a significant portion of his more than 30-year career working with public officials.

Kesti’s work and reputation in these circles have facilitated the growth of a professional network that has come to include members of numerous government agencies, including the FBI. That’s why, over the years, he’s agreed to help those agencies when he can, offering his expertise to connect the dots between events, people and industries the agencies may be interested in. “And that’s a fairly common practice,” he explains. “It’s not a well-known practice, but it’s fairly common. There’s a lot of people in the public that have talents or connections and different agencies utilize them.”

Those agencies have used Kesti’s skills and connections, tapping him at various times to be an asset and a confidential informant; but it wasn’t until after he brought forward suspicions surrounding the finances of a foundation he consulted for led to the arrests of its top brass for embezzlement that the FBI asked him to work as a covert operative.

His work in this role led to the arrests of two sitting mayors in south Florida in 2014. Kesti has furthered his service by speaking to groups such as Rotary International, the Florida State Attorney’s Office, various government entities, high schools, and colleges and universities on ethics and anti-corruption through his “Stand Up” presentation. For his efforts, Kesti has been named the summer quarter’s Mark V. Anderson Character-in-Action™ Leadership Award winner.

Below, he answers The Magazine’s questions about what it was like to work as a covert operative, his motivations for doing so, and why he feels it’s important for others to act when they see something wrong.

How did you become a confidential informant for the FBI in this case? Did the bureau approach you, or did you take information to the bureau?

“They approached me and said, ‘We have had quite a lot of success with you in different areas of the country, and want to go after the epicenter of corruption: South Florida. Miami.’ And I said, ‘Oh. My hometown. Where I’m living.’ But they said ‘There’s a problem. We don’t have anyone at this time that’s being pinched that will cooperate with us, and we can only think of one person that would do this.’ So, I said, ‘Ok, tell me who it is and I will go meet with them and talk them into helping.’ They said, ‘No you don’t understand. The person we need … just needs to be talked into helping us.’ So, I said ‘Ok, what do I do?’ And they said ‘Go home and look in the mirror.’”

Was there a tipping point in your mind where you had been wavering on whether or not to follow through with working as an informant? What made you decide to do so?

“I didn’t even really think about it. I said, ‘When do we start?’ … If your country asks, you just do it. … I always felt these are our government employees trying to do something good for our country. Why not help them? … I come from a family of people that have served in the military and various aspects of the government, and I guess it’s just the way I was brought up.”

How long was it between the time when you agreed to work as a confidential informant to the time when you began the actual work? Were you provided with any sort of training?

“[The preparation work involved] sitting down with some of the agents and developing a plan [for] a fake company and key players in the company who were agents. … It probably took from the time they said will you do this until our first operation … was around four months. And in those four months was some other training that they put me through. … They wanted me to get comfortable with the recording devices, using them, testing them, getting comfortable with my script. In a sense, getting into character. … The other training was more in a sense for security and how to handle a situation if something went sideways.”

I think it gave me a venue to teach a lesson. … People that break law shouldn’t get away with it, and it shouldn’t be tolerated because that’s when societies start to crumble and fall apart. It’s not good for our kids to learn those lessons that you can get away with doing bad things.

Michael Kesti

Was there ever a point where you considered withdrawing from your work? Was that ever an option at any point, if you did feel like it?

“I always had the option of not participating at any time. There were times when I had my real business conflicted with what we were doing, so I would have to scrap an operation for the day. … They always gave me an opportunity that if I wanted to withdraw completely, that was up to me. …. Once I saw the big picture of what they were trying to do, which was trying to eliminate public corruption, I thought it was a good goal.”

Was it difficult for you to keep your life as an undercover informant separate from your “real” life with friends, family, coworkers, etc.? How were you able to compartmentalize those identities?

“If we were approaching someone via a covert operation, I would not also be pursuing business with that person as a client or for a client, in the vast majority of times. So, I didn’t often have that conflict or issue. … Obviously, my friends, my family, nobody knew what I was doing as far as working for the government and that was difficult, but I knew that the ops wouldn’t be successful if they knew — plus there were significant safety issues for my family and friends that I had to consider. My friends in the government knew I was doing it, but very few of them knew I was doing it for multiple government departments. I don’t think any of them in other agencies knew how deep I was in with the bureau doing operative work. I was good at keeping it to myself. I just wouldn’t talk about it.”

How long did you work as a confidential informant in this case?

“The work in Miami went on for two-and-a-half years, because we did multiple operations. We did over 30 operations in south Florida, and a lot of them were going on at the same time in different stages.”

After your covert work concluded, what motivated you to begin presenting on ethics and anti-corruption? Why do you think performing a public service of this sort is important?

“I think it gave me a venue to teach a lesson. … People that break law shouldn’t get away with it, and it shouldn’t be tolerated because that’s when societies start to crumble and fall apart. It’s not good for our kids to learn those lessons that you can get away with doing bad things. Fortunately, my story is an entertaining story. And if I can get their attention to maybe think … [then hopefully they’ll] stand up, do something and take some action.”

A person with good character shows trustworthiness, respect and fairness to others, as well as responsibility and citizenship. Those members who go out of their way to help others and those who overcome obstacles and lead with integrity are good candidates for the Mark V. Anderson Character-in-ActionTM Leadership Award.

Sigma Chi introduced the award to recognize the selfless acts of brothers. A formal recognition by the Fraternity allows non-members to appreciate the scope of the organization. For information about the award, see sigmachi.org/character.