Fittingly, Sigma Chi was born out of a matter of principle. It was the autumn of 1854 at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. One of the 12 members of the Delta Kappa Epsilon chapter on the campus looked for the support of his brothers in his quest to be elected to the office of poet

in one of the school’s literary society, the Erodelphian. He might have assumed a promising result, given that the majority of men in his DKE chapter were also members of the Erodelphian. But four of his brothers declined to cast votes for him in the literary society’s election, instead supporting another Miami student whom they believed possessed superior poetic talents.

This perceived lack of allegiance caused a deep rift among the Dekes, half of whom (including the member in question) felt the candidate deserved their votes on merit or loyalty to a brother, or both. The four dissenters won the moral support of the two remaining Dekes who, though they were not members of the society, admired the dissenters for their courage of conviction.

The feelings on both sides of the argument were so strong that friendships grew apart and the chapter’s meetings and activities were strained and were increasingly rancorous. Wishing to find compromise and reconciliation after months of division, the six brothers who favored reward based on merit proposed a friendly meeting over dinner with the six who believed loyalty should come first.

James Caldwell, Isaac Jordan, Ben Runkle, and Frank Scobey, all member of the Erodelphian Society, joined with Dan Cooper and Tom Bell (who were members of another literary society, the Eccretian, were the six who believed reward should be based on merit. They waited expectantly for the arrival of their estranged Deke brothers, believing that an evening of good food and good company would help restore fraternal bonds. They were to be disappointed.

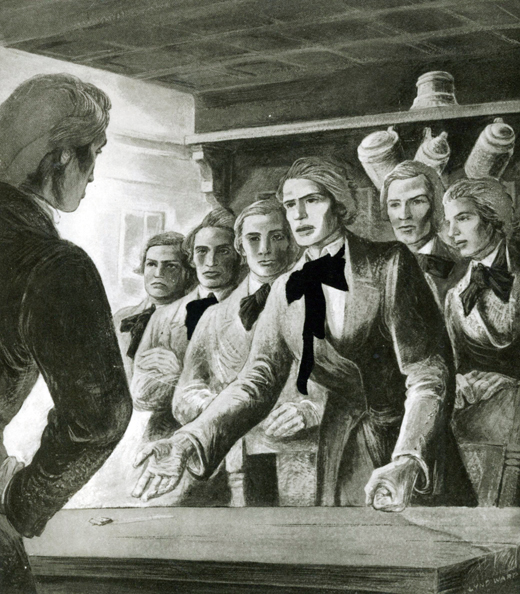

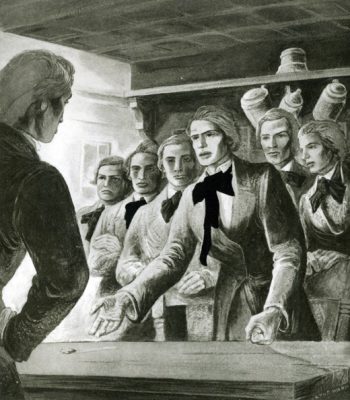

Instead of being joined for the meal by all six of their brothers, only one of them, Whitelaw Reid, appeared. But Reid was not alone. He was accompanied by a Deke alumnus who immediately altered the planned tone of the gathering by announcing sternly, My name is Minor Millikin … I am a man of few words.

True to that statement, he assumed an air of authority and, based solely on a one-sided account of the controversy from Reid, he declared that the six hosts of the evening were wrong on every point, and that the only suitable solution was for the instigators of the rebellion

to be expelled from the Deke chapter, with the others allowed to remain following appropriate chastisement.

This proved to be a turning point for the Deke chapter at Miami of Ohio and a defining moment in the history of Sigma Chi. In response to Millikin’s harsh and undemocratic stance, Ben Runkle dramatically pulled off his Deke badge and tossed it on the table where the conciliatory meal was to have taken place. Looking Millikin in the eye, Runkle fumed, “I didn’t join this fraternity to be anyone’s tool. And that, sir, is my answer!” He stalked out of the room, followed resolutely by his five colleagues, leaving Reid and Millikin to ponder their failed scheme to intimidate the defiant brothers.

Ultimately, that occasion made the schism irreparable. At a meeting several days later, Whitelaw Reid called for the expulsion of all six recalcitrant

brothers from the chapter. With every other vote to expel the members deadlocked due to the equally divided positions, Reid’s new attempt to banish the offending brothers was unsuccessful. Yet it did prove to be the final meeting of the 12 active members of the Kappa Chapter who had begun the school year as Deke brothers.

In April 1855, after prolonged correspondence with Deke’s parent chapter at Yale, Caldwell, Jordan, Runkle, Bell, Scobey and Cooper were expelled from the fraternity. However, those six young men undoubtedly had by that time already shifted their thoughts away from hoping that they would change the minds of those at Deke’s parent chapter, and focused on the prospect of forming a new fraternity.

Given the circumstances, it is no wonder that these men had in mind an organization that believed a commitment to fairness and honesty was key to the success of brotherly friendships. Indeed, the cause of justice became a central idea in the formation of what would become the Sigma Chi Fraternity.

One of the best moves these six ever made was to associate themselves with William Lewis Lockwood. He had entered Miami early in 1855 but had not joined a fraternity. He was the

One of the best moves these six ever made was to associate themselves with William Lewis Lockwood. He had entered Miami early in 1855 but had not joined a fraternity. He was the businessman

of the group and possessed a remarkable organizing ability. More than any other Founder,  he was responsible for setting up the general plan of the Fraternity, much of which endures to this day.

he was responsible for setting up the general plan of the Fraternity, much of which endures to this day.

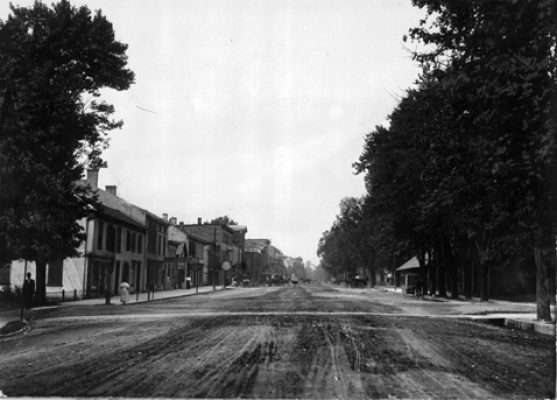

During the latter months of the 1854-55 academic year, Runkle and Caldwell lived in a second-floor room of a building near Oxford’s public square on High Street—now known as the birthplace of Sigma Chi. The Founders held many of the earlier organizational meetings of Sigma Chi in this room, and it was there that Runkle and Lockwood designed the badge. The White Cross was designed exactly as we know it today except for the letters ΣΦ in the black center which were changed to ΣΧ.

With all of their plans formally completed, the Seven Founders of the new Fraternity announced its establishment by wearing their badges for the first time in public on Commencement Day at Miami University, June 28, 1855.

The working fraternal conceptions of Sigma Chi Fraternity have long been identified with the words friendship,

justice

and learning.

These three elements were the basic ideals our Founders used in forming the foundation of Sigma Chi.

In their new fraternity, they held the qualities of congenial tastes, quality fellowship and genuine friendship to be indispensable. The element of thorough fellowship was regarded as a characteristic of all real fraternity endeavors, thus they sought true friendship.

In matters of general college interest, the Founders had refused to be limited simply by the ties of their DKE brotherhood. The Founders’ new association was surely not planned to prevent laudable mutual helpfulness. On the contrary it was designed in every worthy way to enhance such helpfulness. The new fraternity stood for the square deal

in all campus relations. It exalted justice.

In the 19th century, the academics of college were very strenuous. College men of the day studied subjects such as spherical trigonometry; Roman history; odes and satires of Homer, Horace and Plato. A strong emphasis was placed on literature in all campus activities. In the literary exercises of the chapter, literary training was regular and rigid. Founder Issac M. Jordan once said, We entered upon all our college duties with great zeal and earnestness, studied hard, tried to excel in every department of study, contended for every hall or college prize and endeavored to make our Fraternity have a high and honorable standing.

The Founders placed learning in high regard and importance.

More than 100 years ago, Sigma Chi defined fraternity as an obligation, a necessity, an introduction, a requirement, a passport, a lesson, an influence, an opportunity, an investment, a peacemaker and a pleasure.

The Founders’ unfortunate experience in Delta Kappa Epsilon, which they saw as a group focused on conformity for political gain, stirred their hearts and their spirit. They found it a necessity to allow and accept differences in points of views and opinions, realizing that doing so brought opportunities and pleasures. This spirit

became documented as The Spirit of Sigma Chi. Though The Spirit calls for men who are inherently different,

it is expected that the members, in their differences, remain responsible, honorable, gentlemanly, friendly—indeed all those characteristics that are also listed in The Jordan Standard.

For more information on the Founders and the Founding of Sigma Chi:

Told through dynamic interviews and historic reenactment, the enduring values and principles of Sigma Chi come to life.